Event Sourcing Basics

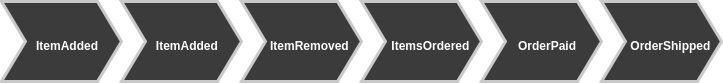

Event Sourcing focuses on business processes. Every write operation in a domain model causes a state change, described by a domain event. For example, an order getting paid is a state change (company gets $$$), and we can describe it with an event using past tense: OrderPaid. We do that for all state changes, and what we get is a series of domain events¹.

Events happen sequentially. They tell us a story about a business process handled by the application.

Thinking in Events

The previous page, "Why Event Sourcing", made a point about database driven designs and how Event Sourcing differs from that. In Event Sourcing, we start with thinking in events.

Every coding tutorial needs a playground. Ours is an eCommerce domain, and our first job is to implement a shopping basket. Business tells us that customers can browse an online shop frontend and add available products to their basket. The customers don't need to be signed in, so their basket is assigned to a shopping session until checkout. So far, so good. But the business wants us to implement realtime stock updates. While browsing the online shop, customers should see constantly updated information about how many other customers have the same products in their basket: "5 other customers want to buy the same product, at the moment". If one customer performs a checkout, stock of the product should be reduced immediately, along with a notification: "Product {name} was bought by a customer from {localization} {time span} ago".

Here is a simplified result of the event storming² session:

As you can see, we have a variety of different events. Not only do we have events that are caused by the customer while interacting with their shopping basket but also events caused by changes in other customers' shopping sessions. We even have two "error events" defined: QuantityStockConflictDetected, ShoppingSessionTimedOut.

Defining Events

In the tutorial introduction we looked at prooph messages and created our first command. Events are just another type of message; hence, each prooph event is an implementation of Prooph\Common\Messaging\Message.

If you do not have the prooph_tutorial project at hand with prooph/common installed, please go back to

the introduction and follow the steps there before continuing with the Event Sourcing tutorial.

We need a project structure for our shopping basket implementation.

|_ Basket

| |_ scripts

| |_ src

| | |_ Infrastructure

| | | |_ Prooph

| | |_ Model

| | | |_ Basket

| | | |_ Command

| | | |_ Event

| | | |_ ERP

| | | |_ Exception

| | |_ Projection

| | |_ Query

| |_ tests

| |_Model

|_ scripts

Run the following command in the prooph_tutorial directory.

$ mkdir -p ./Basket/src/Infrastruture/Prooph \

./Basket/src/Model/Command/ \

./Basket/src/Model/Event/ \

./Basket/src/Model/Basket/ \

./Basket/src/Model/ERP/ \

./Basket/src/Model/Exception/ \

./Basket/src/Projection/Query \

./Basket/tests/Model \

./scripts

Replace composer.json with this version and run composer update:

{

"autoload": {

"psr-4": {"App\\Basket\\": "Basket/src/"}

},

"autoload-dev": {

"psr-4": {"App\\BasketTest\\": "Basket/tests/"}

},

"require": {

"prooph/common": "^4.1",

"prooph/event-sourcing": "^5.2"

},

"require-dev": {

"phpunit/phpunit": "^6.0"

}

}

We just configured composer's autoloader to use the namespace App\Basket for our Basket context and the appropriate

test namespace App\BasketTest.

We've also added the package prooph/event-sourcing to the list of dependencies and told composer to install phpunit/phpunit

when we're in dev mode.

You can guess that prooph/event-sourcing provides the basic implementation needed to develop an event sourced domain model.

Now it's time to define our first domain event. We place all events in ./Basket/src/Model/Event/

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Event/ShoppingSessionStarted.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model\Event;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\BasketId;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\ShoppingSession;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateChanged;

final class ShoppingSessionStarted extends AggregateChanged

{

public function basketId(): BasketId

{

//Note: Internally, we work with scalar types, but the getter returns the value object

return BasketId::fromString($this->aggregateId());

}

public function shoppingSession(): ShoppingSession

{

//Same here, return domain specific value object

return ShoppingSession::fromString($this->payload['shopping_session']);

}

}

Here we extend the base event class AggregateChanged from the prooph/event-sourcing package.

We will discuss aggregates more in a minute, but, first, let's have a look at what the base event class has to offer:

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace Prooph\EventSourcing;

use Assert\Assertion;

use Prooph\Common\Messaging\DomainEvent;

class AggregateChanged extends DomainEvent

{

/**

* @var array

*/

protected $payload = [];

public static function occur(string $aggregateId, array $payload = []): self

{

return new static($aggregateId, $payload);

}

//...

}

AggregateChanged extends Prooph\Common\Messaging\DomainEvent. That's the link back to prooph/common and turns

all events into prooph messages. Keep that in mind, as this is important later when we want to

send events around.

We also see a static factory method called occur that takes an $aggregateId and $payload as arguments.

The $aggregateId is a reference to the corresponding aggregate. Every domain event belongs to exactly one aggregate.

Event Sourced Aggregates

Event Sourced Aggregates are Domain-Driven Aggregates, representing a unit of consistency. They protect invariants. This basically means that an aggregate makes sure that it can transition to a new state. Different business rules can permit or prevent state transitions, and the aggregate has to enforce these business rules.

In our case we need to consider the following business rules:

- A shopping session starts with an empty basket.

- Each shopping session is assigned its own basket.

- A product can only be added to a basket if at least one product is available in stock.

- Product quantity in a basket must not be higher than available stock.

- If stock is reduced by a checkout, product quantity in currently active baskets needs to be checked and conflicts resolved.

- If product quantity in a basket is reduced to zero or less the product is removed from the basket.

- A checkout can only be made if no unresolved quantity-stock-conflicts exist for the basket.

Looking at the rules we can identify a repeating pattern. Every rule includes a state check against a basket and/or describes

a state transition of a basket. With our current understanding of the domain, we're good to go with a Basket aggregate that

enforces the business rules described above.

Even if we name our aggregate Basket, you can think of it as if it were named BasketProcess.

We don't do it that way because it does not reflect the Ubiquitous Language³ which we draw from the language used by the business.

However, when implementing Event Sourcing you can always keep that Process suffix in mind.

Recap: Every state transition is described by an event. Events happen one after another. They tell us a story about a business process. An aggregate is a process consisting of multiple steps happening in a sequence; whereby, each next step is validated by the aggregate upfront using current state:

A checkout can only be made if no unresolved quantity-stock-conflicts exist for the basket.

Effective Aggregate Design¹¹ is possibly the hardest part of a well crafted domain model. And it evolves over time so be prepared to constantly refactor previous design decisions. Thinking of aggregates as processes and modeling them in an event sourced fashion can help a lot, but it remains a task that needs practice. So don't worry if your first attempts end up being unpractical. You will get better. Thinking in events and processes is the key.

Let's add the Basket aggregate now.

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateChanged;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateRoot;

final class Basket extends AggregateRoot

{

protected function aggregateId(): string

{

// TODO: Implement aggregateId() method.

}

/**

* Apply given event

*/

protected function apply(AggregateChanged $event): void

{

// TODO: Implement apply() method.

}

}

Our Basket class extends Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateRoot. This is the base class for all event sourced aggregates.

Later we'll also look at an alternative approach using traits instead of extending a prooph class, but the

version shown here is easier to understand and helps us with the first steps. AggregateRoot is an abstract class and asks us to implement

two methods aggregateId(), which should provide the string representation of the globally unique identifier of the aggregate,

and an apply() method.

The apply() method is best explained with an example so let us dive into the implementation. Each aggregate has a

lifecycle. To start such a lifecycle we need to create the aggregate. But prooph's AggregateRoot does not allow creating the class constructor as a public method. Instead, we're asked to use a so-called named constructor, aka static factory method.

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model;

use App\Basket\Model\Event\ShoppingSessionStarted;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\BasketId;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\ShoppingSession;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateChanged;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateRoot;

final class Basket extends AggregateRoot

{

public static function startShoppingSession(

ShoppingSession $shoppingSession,

BasketId $basketId)

{

//Start new aggregate lifecycle by creating an "empty" instance

$self = new self();

//Record the very first domain event of the new aggregate

//Note: we don't pass the value objects directly to the event but use their

//primitive counterparts. This makes it much easier to work with the events later

//and we don't need complex serializers when storing events.

$self->recordThat(ShoppingSessionStarted::occur($basketId->toString(), [

'shopping_session' => $shoppingSession->toString()

]));

//Return the new aggregate

return $self;

}

protected function aggregateId(): string

{

// TODO: Implement aggregateId() method.

}

/**

* Apply given event

*/

protected function apply(AggregateChanged $event): void

{

// TODO: Implement apply() method.

}

}

A meaningfully named constructor using the Ubiquitous Language is a great way to let the code document itself.

The Basket aggregate requires a ShoppingSession and a BasketId to start the shopping session.

Both are value objects that we're going to add next.

Note: BasketId becomes the identifier of the aggregate but it is created outside of the aggregate. That's a common pattern in a CQRS system. For example the frontend can create a BasketId using a JavaScript UUID library and send the BasketId to the backend. Remember from the introduction chapter: Handling a command has no response other than success or failure. In case of success, the frontend can use the BasketId to fetch state of the Basket from a read model. Later in the tutorial we'll see that in action. For now, just keep in mind that aggregate ids are created by the client or application layer if a CQRS architecture is used.

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket/ShoppingSession.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model\Basket;

final class ShoppingSession

{

private $shoppingSession;

public static function fromString(string $shoppingSession): self

{

return new self($shoppingSession);

}

private function __construct(string $shoppingSession)

{

if($shoppingSession === '') {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException("Shopping session must not be an empty string");

}

$this->shoppingSession = $shoppingSession;

}

public function toString(): string

{

return $this->shoppingSession;

}

public function equals($other): bool

{

if(!$other instanceof self) {

return false;

}

return $this->shoppingSession === $other->shoppingSession;

}

public function __toString(): string

{

return $this->shoppingSession;

}

}

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket/BasketId.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model\Basket;

use Ramsey\Uuid\Uuid;

final class BasketId

{

private $basketId;

public static function fromString(string $basketId): self

{

return new self($basketId);

}

private function __construct(string $basketId)

{

if(!Uuid::isValid($basketId)) {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException("Given basket id is not a valid UUID. Got " . $basketId);

}

$this->basketId = $basketId;

}

public function toString(): string

{

return $this->basketId;

}

public function equals($other): bool

{

if(!$other instanceof self) {

return false;

}

return $this->basketId === $other->basketId;

}

public function __toString(): string

{

return $this->basketId;

}

}

Recap: We used a named constructor to create the Basket aggregate. The named constructor defines the requirements needed

to start a shopping session, namely the ShoppingSession and BasketId. Instead of setting those value objects as properties

in the Basket aggregate we record the first domain event, ShoppingSessionStarted, of the aggregate.

Now the apply() method comes into play. Our Basket aggregate will have many more methods later to deal with all the things

happening during a shopping session, and in those methods we will often need the current state of the aggregate to

protect invariants. To get access to the state we need to apply() recorded domain events in the exact same order as

they were recorded. Prooph's AggregateRoot takes care of the latter but it does not know how a domain event should

be applied. Hence, we need to take over that task.

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model;

use App\Basket\Model\Event\ShoppingSessionStarted;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\BasketId;

use App\Basket\Model\Basket\ShoppingSession;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateChanged;

use Prooph\EventSourcing\AggregateRoot;

final class Basket extends AggregateRoot

{

/**

* @var BasketId

*/

private $basketId;

/**

* @var ShoppingSession

*/

private $shoppingSession;

public static function startShoppingSession(ShoppingSession $shoppingSession, BasketId $basketId)

{

$self = new self();

$self->recordThat(ShoppingSessionStarted::occur($basketId->toString(), [

'shopping_session' => $shoppingSession->toString()

]));

return $self;

}

protected function aggregateId(): string

{

// TODO: Implement aggregateId() method.

}

/**

* Apply given event

*/

protected function apply(AggregateChanged $event): void

{

//A simple switch by event name is the fastest way,

//but you're free to split things up here and have, for example, methods like

//private function whenShoppingSessionStarted()

//To delegate work to them and keep the apply method lean

switch ($event->messageName()) {

case ShoppingSessionStarted::class:

/** @var $event ShoppingSessionStarted */

$this->basketId = $event->basketId();

$this->shoppingSession = $event->shoppingSession();

break;

}

}

}

Now that we have access to the current state, we can finally implement the aggregateId() method to fulfill the contract

defined by prooph's AggregateRoot class.

File: ./Basket/src/Model/Basket.php

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace App\Basket\Model;

//...

final class Basket extends AggregateRoot

{

/**

* @var BasketId

*/

private $basketId;

/**

* @var ShoppingSession

*/

private $shoppingSession;

public static function startShoppingSession(ShoppingSession $shoppingSession, BasketId $basketId)

{

//...

}

protected function aggregateId(): string

{

//Return string representation of the globally unique identifier of the aggregate

return $this->basketId->toString();

}

/**

* Apply given event

*/

protected function apply(AggregateChanged $event): void

{

//...

}

}

Ok, those are the basics of Event Sourcing. Many new things to learn, right? But don't worry. You'll get used to it while we look at some more aspects of Event Sourcing. In the next part we will look at testing event sourced aggregates, which is super easy when you have a clean and decoupled domain model.

Advice: Revisit the basics part whenever you feel lost. Event Sourcing is really simple once you understand it. In the section below you will find links to related blog posts. Before you follow them, take a break and let the basics sink in. You can read the posts later when you feel more comfortable with Event Sourcing. Don't overload your head with too much information at once.